Editor’s Note: Americans United gets a lot of questions. When AU staff members are speaking at public events, a question-and-answer session is customary. In addition, AU receives questions regularly by email, through social media and via letters.

We’ve noticed that certain questions seem to come up repeatedly. This article provides answers to these most commonly asked questions.

Question: Was the United States founded to be an officially Christian nation?

Answer: No, it was not. Christian Nationalists have long peddled a myth about America’s alleged Christian origins, but it is precisely that — a myth.

If an officially Christian nation had been the intent of our founders, the Constitution would say that front and center. But it does not. Therefore, the best answer to claims that the United States was founded to be a Christian nation is, “Where does it say that in our Constitution?” It simply isn’t in there.

The U.S. Constitution:

A secular document (Getty Images)

As AU notes on its website, “The U.S. Constitution is a wholly secular document. It contains no mention of Christianity or Jesus Christ. In fact, the Constitution refers to religion only twice: in the First Amendment, which bars laws ‘respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,’ and in Article VI, which prohibits ‘religious tests’ for public office. Both of these provisions are evidence that the country was not founded as officially Christian.” (For more on this, visit: www.au.org/about-au/history/is-america-a-christian-nation/ and au.org/what-did-the-founding-fathers-really say/.)

Question: Did America’s founders really pioneer the separation of church and state?

Answer: Absolutely. Combinations of religion and government were common throughout much of human history. The most dissenters could hope for was the extension of a measure of toleration. Some countries retained official churches while extending toleration, but that’s not separation of church and state. Until America’s founders crafted the First Amendment, no nation had dared to put an official distance between religion and government.

This did not happen in a vacuum. Key founders such as Thomas Jefferson and James Madison were keen students of history and were well aware of the situation in Europe, where hundreds of years of church-state union led to violence, terror, torture and war.

In his “Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments” (1785), Madison remarked on this unfortunate history, observing, “Torrents of blood have been spilt in the old world, by vain attempts of the secular arm, to extinguish Religious discord, by proscribing all difference in Religious opinion. Time has at length revealed the true remedy. Every relaxation of narrow and rigorous policy, wherever it has been tried, has been found to assuage the disease.”

Question: Does the religious language in the Declaration of Independence mean the founders disagreed with church-state separation?

Answer: No, it does not. It’s important to know the history of the Declaration of Independence and why it was written. The Declaration contains four religious references — “the Laws of Nature and Nature’s God,” “Creator,” “the Supreme Judge of the world” and “divine Providence.”

The main thing you notice about these phrases is that they are not Christian — they’re all deistic references. Furthermore, Thomas Jefferson, who authored the Declaration, is responsible only for the first one. The other three were added by an editing committee.

In his book The Founding Myth: Why Christian Nationalism Is Un-American, Americans United Vice President of Strategic Communications Andrew L. Seidel deconstructs each phrase, noting that while Christian Nationalists may assume that these references refer to their god, there is no evidence that they do.

“The references are not biblical,” Seidel writes. “At the time, there were about eleven major English versions of bibles that the founders could have borrowed verbiage from. Two of the phrases, ‘divine Providence’ and ‘Nature’s God,’ do not appear in any of those bibles. Nor does the phrase ‘Supreme Judge of the World,’ though the bible does occasionally speak of its god as a judge. … And, of course, the Judeo-Christian god is described as a creator — in Genesis and at least five times outside the Genesis story — but every religion that describes a creator-god and deism is defined solely by a belief in a cosmic creator-god. Scholars can argue forever about whether the references are deist or theist, but we can all be sure that they are not Christian.”

It’s also important to remember the purpose of the Declaration: It’s not a governance document. The Declaration was an announcement to the world that our nation intended to sever its ties to Great Britain and be independent. Its words are undoubtedly powerful, but it says nothing about the structure of government the United States would adopt. That came later when the founders drafted the Constitution, a wholly secular document that does not contain the words “Christian,” “Jesus” or “God.”

Question: How did the religion clauses of the First Amendment come about?

Answer: The church-state separation provisions of the First Amendment were heavily influenced by the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. Introduced by Thomas Jefferson in 1776, the Virginia Statute did two things: It disestablished the Anglican Church in Virginia, and it guaranteed to everyone the right to worship as they saw fit.

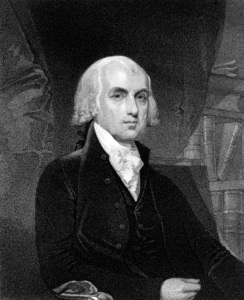

James Madison: Father of the Constitution and church-state separation advocate (Getty Images)

The Virginia Statute did not become law until 1786, and it was guided through the legislature by Jefferson’s friend and political ally James Madison. (Jefferson was serving as U.S. ambassador to France at the time and living in Paris.) Madison, who is called the “father of the Constitution,” took the two key principles of the Virginia Statute — no official establishment of religion and freedom of worship for all — and built them into the First Amendment, of which he was a primary author.

Question: What is Article VI of the Constitution, and why is it relevant to this debate?

Answer: Article VI, Section III of the Constitution deals with Oaths of Office. It mandates that elected federal and state lawmakers as well as executive officials and judges “shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support this Constitution” and goes on to say, “but no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.”

At the time the Constitution was drafted, some states required public officeholders to hold certain religious beliefs. They might, for example, have to be professing Christians or affirm a belief in God. Article VI makes it clear that no such religious requirements will be applied to federal office. This opens federal office up to Christians and non-Christians. A provision like this reinforces the separation of church and state; it simply cannot be reconciled with the idea of an officially “Christian nation.”

The “no religious test” language was championed by Charles Pinckney, a delegate to the Constitutional Convention from South Carolina. Pinckney was critical of state-established churches. During a speech to the Continental Congress, he blasted the established church of Great Britain, remarking, “How many thousands of subjects of Great Britain at this moment labor under civil disabilities merely on account of their religious persuasions!”

Question: What did Thomas Jefferson mean when he invoked the “wall of separation” metaphor?

Answer: While serving as president, Thomas Jefferson received a letter from a Baptist association in Danbury, Conn., commenting on religious freedom. The Baptists, who were living under a form of Congregationalist theocracy, knew that Jefferson was an advocate of religious freedom and wrote to express their hope that one day his views would carry the day in the states, and they would then be free from an established church. (At the time, the religious freedom provisions of the First Amendment applied only to the federal government. States were free to maintain official churches, and several did.)

Jefferson’s reply, dated Jan. 1, 1802, was carefully crafted. Aware that the contents of the letter would likely become public, Jefferson used his response to craft a major statement of his views on religious freedom. He consulted with his attorney general and other cabinet officials as he worked on a draft.

In this letter, Jefferson agreed with the Baptists on the importance of religious freedom and tied that principle to church-state separation, writing, “Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, & not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should ‘make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,’ thus building a wall of separation between Church & State.”

This powerful metaphor has rung down through the ages.

Question: What were the founders’ personal religious beliefs?

Answer: Like Americans today, the founders reflected religious diversity in their personal beliefs. Some were Christians, some were Unitarians, some were Deists and others are hard to categorize. But despite what their personal beliefs might have been, key founders agreed that separation of church and state was the best policy for our new nation.

It’s worth noting that the founders’ beliefs about religion and God do not prove or even illuminate the principles on which they founded this nation. Personal theistic beliefs do not assume control over other ideas generated by the mind.

Question: When did “In God We Trust” become the United States’ official motto?

Answer: “In God We Trust” was designated the country’s official motto in 1956 thanks to a law passed by Congress and signed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Prior to that, the nation didn’t have an official motto, although the Latin phrase “E Pluribus Unum” (“Out of Many, One”) filled that role unofficially and appeared on the Great Seal of the United States, adopted in 1782.

‘In God We Trust’: Its roots don’t go back to the founding period (Getty Images)

The phrase “In God We Trust” does not have roots in the founding period. The first coin officially minted by the U.S. government, the Fugio cent of 1787, contained the phrase “Mind your business.”

“In God We Trust” wasn’t proposed as a contender until the Civil War. A minister in Pennsylvania wrote to Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase and suggested the country use “Almighty God in some form on our coins.” Chase liked the idea and initially toyed with “God Is Our Trust,” which he later tweaked to “In God We Trust.” The phrase first appeared on a two-cent piece issued in 1864. It was used on coins sporadically until 1955, when Congress passed a law mandating its use on all U.S. currency.

The move to adopt the religious statement as the country’s official motto came during the height of the Cold War. Proponents argued that an explicit reference to God would set the United States apart from the Soviet Union, which was officially atheistic.

“In these days when imperialistic and materialistic communism seeks to attack and destroy freedom, we should continually look for ways to strengthen the foundations of our freedom,” U.S. Rep. Charles Edward Bennett (D-Fla.) said while introducing a bill to designate the motto.

Question: Did all states have official prayer and Bible reading in public schools prior to the 1962 and 1963 U.S. Supreme Court rulings declaring such practices unconstitutional?

Answer: Prior to 1962, school-sponsored, coercive forms of school prayer and Bible reading were not as common in public schools as some people think.

In 1960, Americans United undertook a survey of Bible reading in public schools. The organization found that only five states had laws on the books mandating Bible reading in public schools. Twenty-five states allowed Bible reading as an option for local districts but did not require it. In 11 states, courts had declared the practice unconstitutional. (The remaining states had no laws on the books one way or the other.)

Several state supreme courts had struck down coercive forms of religious activity in public schools prior to the U.S. Supreme Court’s rulings. Among them were Wisconsin (1890), Nebraska (1903) and Illinois (1910).

Question: Did the school prayer rulings ban all forms of religious activity in public schools?

Answer: They did not. It’s important to remember that the Supreme Court has never struck down truly voluntary prayer in public schools; it only invalidated school-sponsored practices that required participation, declaring them coercive.

Public school students have the right to take part in voluntary religious activity that does not cause a disruption or infringe on the rights of others. They may pray silently during the school day, read religious books during their free time and talk about religion with willing friends. Many schools have voluntary religious clubs alongside other types of student-run organizations.

In addition, public schools may teach about religion objectively as an academic subject and discuss its role on history, art and literature. (For more on this topic, visit www.au.org/knowyourrights/).

Question: How does church-state separation protect rights other than religious freedom?

Answer: Since its founding in 1947, Americans United has made it clear that separation of church and state is the linchpin of many of our rights, not just religious freedom. In the 1950s, AU opposed laws that banned birth control on religious grounds, and today the organization argues that abortion policy should not be based on religious rationales.

AU has also opposed religiously based censorship. Banning of books, magazines, films and stage plays because some religious groups found the content objectionable was a common problem in the past, and AU opposed it; even today, we are seeing a new wave of book-banning sparked in part by religious objections to content.

Church-state separation also protects LGBTQ+ rights. Arguments against marriage equality, for example, were often anchored in religious belief. Americans United argues that if a law lacks a secular legislative purpose, it should not stand. (The Supreme Court agreed with this position until recently.)

Question: Do Americans support separation of church and state?

Answer: A poll conducted by Americans United in 2019 found strong support for church-state separation among the American people, with 60% of poll respondents saying protecting the separation of religion and government is either one of the most important things to them personally or very important. Only 9% said it was not too important.

Furthermore, nearly half of likely voters in 2020 — 47% — said they would be more likely to support a candidate who announced support for church-state separation. Only 11% said backing separation would make them less likely to support a candidate. Support for pro-separation candidates was shared in all parts of the country — even in the Bible Belt South.

Other polls have found similar results. A poll released in October 2021 by the Pew Forum found that many more Americans favor separation of church and state than oppose it. Pew reports that 55% of Americans are considered to be either “strong” or “moderate” supporters of church-state separation (28% strong, 27% moderate). 18% fall into a “mixed” category, meaning they sometimes back a church-state separation position but just as often do not, depending on the issue. Pew says that 14% of Americans are “integrationists” — a term Pew applied to people who favor little or no separation of church and state. (The remaining 12% had no opinion.)

Furthermore, 54% of Americans agree that the federal government should enforce separation of church and state, while 19% said the government should stop enforcing it. The rest, 27%, had no opinion.