Last March, Suzette Baker, the head librarian at a Llano County, Texas, branch library, was fired for — in the words of her boss — “creating a disturbance, insubordination, violation of policies and failure to follow instructions.”

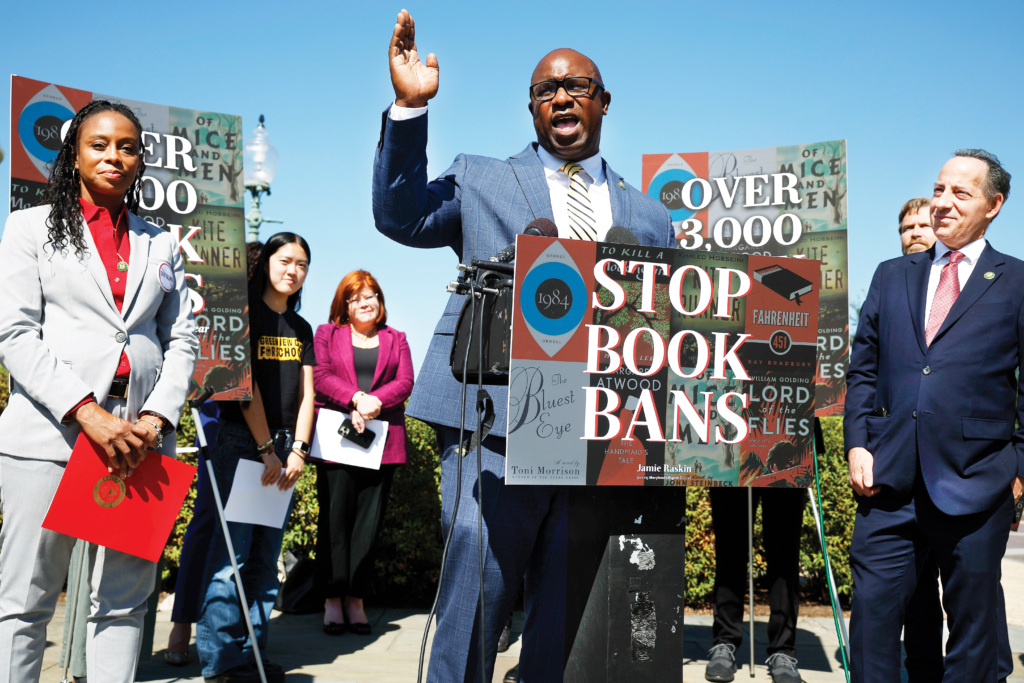

Free to learn: (from left) U.S. Reps. Shontel Brown, Jamaal Bowman and Jamie Raskin denounce book banning at Capitol Hill event (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Baker’s failing or crime? She refused to remove books a group of local residents complained were “pornographic” and “inappropriate.”

“The books in my library in Kingsland were not taken off the shelves, we did not move them. I told my boss that was censorship,” Baker told a reporter from KXAN-TV in Austin.

Baker noted that one of the books targeted was about the life of a transgender teen, remarking, “It is her biography of her life growing up. … Obviously this group thought that was too much for their children to read, which no one is forcing their kids to read anything.”

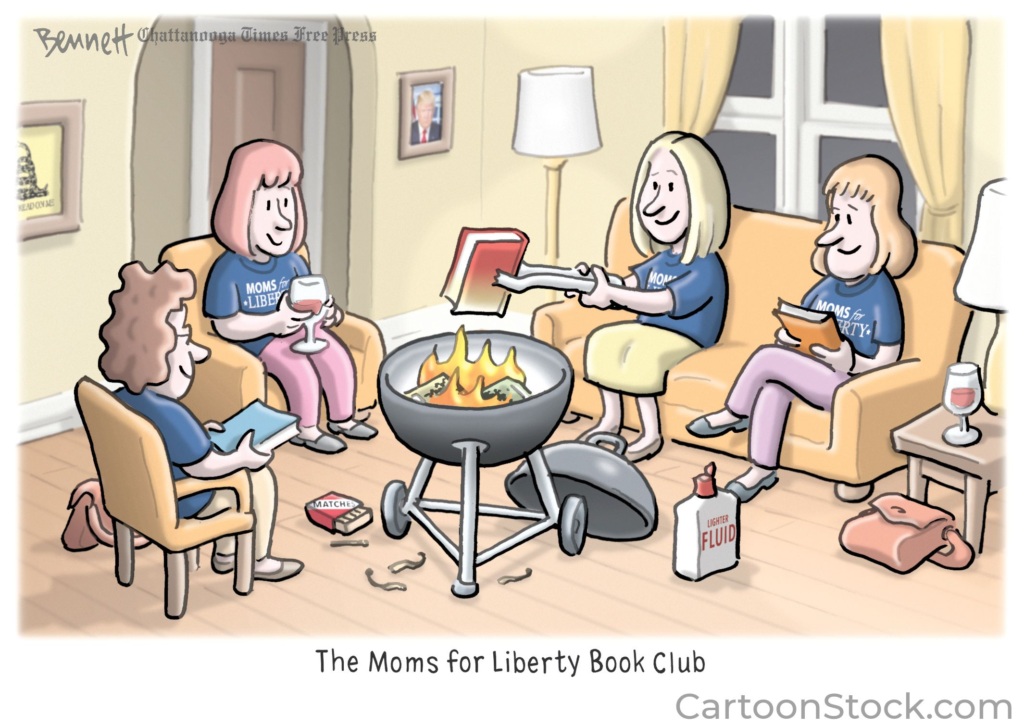

In Spotsylvania County, Va., some members of the school board were so incensed by books in the school library that they advocated setting them ablaze.

“I think we should throw those books in a fire,” board member Rabih Abuismail said. “I guess we live in a world now that our public schools would rather have kids read about gay pornography than Christ.”

Another member, Kirk Twigg, explained that he wanted to “see the books before we burn them so we can identify within our community that we are eradicating this bad stuff.”

Making matters even scarier, state legislatures have adopted 110 bills that PEN America, a group that defends freedom of expression, identifies as “educational gag orders,” and 10 became law. PEN further notes, “Four more gag orders were imposed via executive order or state or system regulation: two in Florida, and one each in Arkansas and California. These developments bring the number of educational gag orders that have become law or policy to a total of 40 across 22 states as of November 1, 2023.”

Librarians and teachers across the country are worried that the slowly brewing culture war against the “unacceptable” is spreading. This is an effort that seeks to “ban,” “remove” and “challenge” books, movies, magazines, art and other forms of creative expression. They fear this effort could lead to arrest and imprisonment — or worse — for anyone hosting such works. A growing number of state and localities across the country — including in Florida, Michigan, Idaho, Arkansas, Indiana, Missouri, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania and Texas — are pursuing legislation to impose fines or imprisonment, or both, for school employees and librarians.

John Chrastka, executive director of EveryLibrary, a group that helps libraries oppose censorship, told Church & State that three factors — or “vectors” —are driving the current banning and censorship campaigns. One is that “political actors are looking to signal their base that they are doing something with a new agenda, identifying new supporters, and building up their own credibility among their political base.” Second, they are “utilizing the book challenge approach to advance other agendas — whether they are anti-union, anti-public-sector workforce, anti-tax.” Chrastka insists that “there is really no legitimacy for the book ban issue — it’s a wolf in sheep’s clothing, a Trojan horse.” And finally, there is “parental control, parental concern, and that is certainly a moralistic agenda attached to it as well.”

Chrastka stresses that if book banners can “criminalize the content, they can do two things.” First, they can “criminalize the humans that the books represent” and, second, they can “make it illegal to teach it, [and] thus they criminalize the moral issue they oppose, like gender studies or sex ed.” The three vectors combined, he said, “are defining the banning issue for American history, especially K through 12th grade.”

What’s happening with books is intense, but it’s not new. The U.S. is in the middle of a deep political crisis that has been brewing since the 1970s with the emergence of what’s called the “culture wars.”

It is an era framed by two pivotal Supreme Court decisions — the landmark reproductive rights ruling in Roe v. Wade (1973) that was overturned a half-century later by Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022). Today’s mounting censorship war — and the growing fears among librarians and teachers of being arrested — is another aspect of the culture wars; it’s a blazing inferno that’s often fueled by Christian Nationalist groups that want to suppress anything that offends their faith.

As a result, book bans are soaring in number. PEN America reports during the year from July 1, 2022, to June 30, 2023, there were 3,362 instances of book banning in public school classrooms and libraries. This is a 38% increase from the year prior.

The organization notes that book bans are spreading throughout the country, with 1,406 in Florida; 625 in Texas; 333 in Missouri; 281 in Utah; and 186 in Pennsylvania. Sadly, additional bans in more states are likely in school year 2023-2024. PEN stresses that the books most “targeted” are by/about females, people of color and/or LGBTQ+ individuals.

It should be noted that not all challenges to books are successful — but all have a chilling effect. PEN defines book banning as “any action taken against a book based on its content and as a result of parent or community challenges, administrative decisions, or in response to direct or threatened action by lawmakers or other governmental officials, that leads to a previously accessible book being either completely removed from availability to students or, where access to a book is restricted or diminished.”

The group argues, “Amid a growing climate of censorship, school book bans continue to spread through coordinated campaigns by a vocal minority of groups and individual actors and, increasingly, as a result of pressure from state legislation.”

PEN found that 30% of banned books included characters of color and themes of race and racism; 30% represented LGBTQ+ characters or themes; and 6% percent included a transgender character. Among the most banned books are Ellen Hopkins’ Tricks (33 bans), Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye (29 bans) and John Green’s Looking for Alaska (27 bans).

“It’s disappointing to see such a steep rise in the banning and restriction of books,” Green told the U.K.’s The Guardian newspaper. “We should trust our teachers and librarians to do their jobs. If you have a worldview that can be undone by a book, I would submit that the problem is not with the book.”

The American Library Association (ALA) documented 1,269 demands to censor library books and resources in 2022. It reports this to be “the highest number of attempted book bans since ALA began compiling data about censorship in libraries more than 20 years ago.” ALA defines censorship as “[l]imiting or removing access to words, images, or ideas. The decision to restrict or deny access is made by a governing authority. This could be a person, group, or organization/business.”

“A year, a year and a half ago, we were told that these books didn’t belong in school libraries, and if people wanted to read them, they could go to a public library,” Deborah Caldwell-Stone, the director of the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, noted. “Now, we’re seeing those same groups come to public libraries and come after the same books, essentially depriving everyone of the ability to make the choice to read them.”

America has had a long, disturbing history battling what some consider unacceptable. In 1624, John Morton arrived in what is now known as Quincy, Mass., and a decade later, this apparently rakish fellow (for his day) published New English Canaan (1627), what today would be called an exposé. One critic called it “a harsh and heretical critique of Puritan customs and power structures that went far beyond what most New English settlers could accept.” It is the nation’s first banned book; it would not be the last.

In 1814, Thomas Jefferson blasted efforts to ban a French book titled La création du Monde by Regnault de Bécourt. The book contained some passages criticizing religion, and Nicolas Dufief, a Philadelphia book dealer, was accused of blasphemy for having sent it to Jefferson at de Bécourt’s request.

In a letter to Dufief, Jefferson lashed out, writing, “I am really mortified to be told that, in the United States of America, a fact like this can become a subject of inquiry, and of criminal inquiry too, as an offense against religion; that a question about the sale of a book can be carried before the civil magistrate. Is this then our freedom of religion? And are we to have a censor whose imprimatur shall say what books may be sold, and what we may buy?”

Decades later, the social and economic changes that followed the Civil War were traumatic and far-reaching. In the face of these challenges, a powerful movement emerged that attempted to contain the forces that were perceived as threatening moral order. It railed against vice in every form, be it alcohol consumption, gambling, prostitution, birth control or alleged obscenity in the arts.

The Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) and the Women’s Christian Temperance Alliance (WCTA), among others, championed this movement. The leader of this moral campaign was noted vice crusader Anthony Comstock.

In 1868, just three years after the end of the Civil War, Comstock’s movement secured its first major victory when the New York state legislature passed an incredibly broad law to suppress what was described as “obscene” materials. Five years later, the movement was strong enough to have the U.S. Congress enact the “Act for the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use.” The 1873 statute became popularly known as the Comstock law.

The law was so effective that within the first six months of passage, Comstock boasted that it led to the seizure of 194,000 pictures and photographs, 14,200 stereopticon projector plates and 134,000 pounds of books and other media. In the 1910s, near the end of his life, Comstock claimed that he had destroyed nearly 4 million photographs and 160 tons of “obscene” literature. The most inspired anti-obscenity campaign involved Comstock’s arrest of Ezra Heywood for mailing a publication that included two Walt Whitman poems and description and/or illustration of a contraceptive device called “The Comstock Syringe.”

The 20th century saw wave after wave of censorship campaigns. The 1920s was marked not only by the Palmer raids against socialists and the deportation of anarchists, but the banning, in New York, of James Joyce’s Ulysses and, in Boston, D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Sinclair Lewis’ Elmer Gantry. The era also saw Catholic leaders promote state censorship bills in an effort to “clean up” Hollywood movies and included the famous 1925 Scopes trial in Tennessee over teaching evolution.

In the mid-1940s through the mid-’50s, comic books were subject to repeated waves of censorship campaigns that took place at both the city and state level in what can best be described as a moral panic.

During a two-year period, 1947-49, more than 100 cities across the country, big and small, passed laws or ordinances to ban the display or sale of comic books. In late 1953, the comic book wars moved to the U.S. Senate, which established a special subcommittee to investigate “juvenile delinquency.” Sen. Estes Kefauver (D-Tenn.), an ambitious politician who became his party’s vice-presidential candidate in 1956, led the charge against comic books, which he and many others linked to juvenile crime. The anchor of Kefauver’s ire was Mad magazine.

Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, there was a censorship campaign on a grand scale. Although widely regarded as a liberal, U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy relied on the old Comstock law in his victorious 1962 censorship battle against Ralph Ginzburg and Eros magazine, which published erotica. The FBI subsequently initiated the Library Awareness Program in which agents visited libraries to check on the identities of people examining potentially controversial materials. The FCC also fined more than a dozen radio stations and one television station for broadcasting “obscene” programming.

In the 1980s, the nation saw campaigns to block the exhibitions of artistic works by Robert Mapplethorpe and Andres Serrano (the latter’s work “Piss Christ” was called blasphemous), as well as attempts in some areas to block the screening of Martin Scorsese’s film “The Last Temptation of Christ.” Around the same time, a constitutional amendment to ban flag burning by labeling it a form of desecration gained steam. The measure failed to clear Congress, and the Supreme Court invalidated state laws that criminalized flag burning, calling them violations of free speech.

Today’s book-censorship campaign is being promoted by a panoply of groups, some with Christian Nationalist overtones, such as Moms for Liberty, No Left Turn in Education and Parents Defending Education.

PEN notes that Moms for Liberty consists of 284 chapters in over 44 states. Citizens Defending Freedom claims 20 local affiliates (primarily in Texas and Georgia), and Parents’ Rights in Education has local affiliations in 15 states.

A separate group, the National Center on Sexual Exploitation (formerly Morality in Media), has drafted model legislation designed to block access to “pornography,” a term it defines broadly, labeling it “a social and physical toxin that destroys relationships, steals innocence, erodes compassion, breeds violence and kills love.” Since 2013, the organization has released an annual “Dirty Dozen” list that, in 2022, included such familiar and popular sites as Netflix, Etsy, Google, Meta (i.e., Facebook), Reddit and Twitter (now renamed X), among others.

The book-banning and censorship wars are part of the larger culture wars driven by white evangelical Christians, a key part of the Republican activist base. They are waging an apparently coordinated campaign against reproductive rights, LGBTQ+ rights and “critical race theory,” a label they pin on any study or investigation of racial discrimination.

But despite the wave of censorship washing over the nation, some good news stands out: Americans don’t support banning books. A survey commissioned by the EveryLibrary Institute found that three-quarters of Americans opposed book banning. EveryLibrary’s Chrastka notes, “Book banners are only in the 8-10 percent, based on all the survey work I’ve seen and what we have done. It’s only a minority of people interested in the weaponized and politicized book banning and censorship challenges.”

Chrastka argues that there are “three vectors or approaches to coalition work as well as individual and collective action.” He believes the fight against book banning and censorship implicate core American values.

The first vector, Chrastka said, involves “civil liberties, [and discussion] of what the separation of church and state truly means.”

The second is “civil rights.” He insists, “book bannings are happening because of gender identity, sexual identity or even racial or religious identity.” He goes further, insisting, “If we are not turning away people from the library’s front door because of the color of their skin, then why are we taking their books off the shelf? If you are wearing a rainbow flag on your lapel and we can’t turn you away from the front door, then why are we banning your titles?”

The final vector comprises what Chrastka identifies as “civil society,” the idea that a community’s public library and public schools “are two of the civil infrastructure points, community institutions, and we must be very clear as [to] what these attacks are in terms of structur[ing] of society.”

The campaign against book-banning and censorship is taking many forms. One involves a coalition of library and civil-liberties groups — including Americans United, the American Library Association, American Civil Liberties Union, Association of American Publishers and National Education Association — having formed United Against Book Bans to contest the banning.

(Madelyn Kelly)

Another involves homegrown groups across the country that are challenging local banning efforts. For example, in March, a coalition of residents in the Escambia County, Fla., School District challenged school officials over the removal of 10 books and restriction of 100 others from the school library. They argued that the action violated students’ First Amendment rights when they removed books that discussed race, racism and LGBTQ+ people.

In Carver County, Minn., a resident last fall demanded the removal of Gender Queer: A Memoir by Maia Kobabe, an often-challenged title. Members of the community got wind of what was going on and packed a meeting of the library board to oppose pulling the book. The board voted unanimously to keep it on the shelves.

Still another approach involves legal challenges. In July, a coalition including Texas Library Association filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas, Austin Division, challenging a new Texas law, HB 90, requiring all vendors to review and rate millions of books and other library materials according to sexual content. On Aug. 31, one day before the law was set to take effect, the court blocked enforcement of the bill as a violation of the First Amendment.

In late November, Penguin Random House joined several authors and educators in filing a federal lawsuit challenging a new Iowa law that bans practically any book that has sexual content from school libraries. (The law exempts religious texts to avoid banning the Bible.)

Most inspiring, student-led banned book clubs and anti-censorship groups have formed in many states. In Miami, 16-year-old Iris Mogul started a banned book club, asserting, “I thought it would be perfect to do a banned book club — one, as just a way to read beautiful literature that’s important and should be read and then two, kind of as an act of resistance.”

In Austin, high school senior Ella Scott began leading a banned book club when she first learned about attempts to challenge and censor certain stories. “It’s happening in our classroom, but students don’t have a voice,” she said.

In Sherman, Texas, the local school board attempted to stop a high school production of the musical “Oklahoma!” because a transgender student was cast in a lead role. The board demanded that only students “born as females [be cast] in female roles and students born as males in male roles.” However, after much local protest, the school district reversed course and voted unanimously to restore the original casting.

Americans United has opposed religion-based censorship since its founding in 1947, and today continues to defend the right to read and learn.

“Christian Nationalists want to use a narrow definition of faith to erase the existence and experiences of entire groups of people and whitewash our history,” said AU President and CEO Rachel Laser. “Nothing less than our ability to read about, experience — and ultimately understand — the world around us is at stake.”