Voters in Arizona in November rejected a plan to expand private-school vouchers in the state by 65 to 35 percent. The lopsided results might have been a surprise to school-voucher boosters, but they shouldn’t have been. Vouchers and other forms of private-school aid plans have been getting trounced at the ballot box since 1967.

These proposals have taken many forms over the years. Some were efforts to remove state constitutional provisions that bar taxpayer funding for religious institutions, thereby opening the door to vouchers by legislative action. Others would have established sweeping voucher plans and/or allowed other types of public aid to private religious schools. No matter what form they took, all were turned back by voters.

Here’s a look at the historical high-profile Election Day battles over taxpayer aid to private and religious schools:

New York, 1967: A group of state legislators, working in conjunction with lobbyists for the Catholic Church, spent more than a year writing a package of revisions to the state constitution. One of their proposals would have removed Article XI, Section 3 of that document, which bans allocating taxpayer money for religious purposes. Americans United organized a series of public meetings throughout the state to educate residents and joined with public-school advocates to make it clear what was at stake. On Election Day, 72 percent of voters rejected the changes. The plan failed to pass in any of New York’s 62 counties.

Michigan, 1970: Groups supporting public education, along with Americans United and several religious organizations, promoted an amendment to the state constitution that would bar tax aid to religious institutions. Officials of the Catholic Church, the Missouri Synod Lutheran Church, the Christian Reformed Church and several business groups urged voters to reject the amendment, but it passed 57-43 percent.

Nebraska, 1970: Officials with the Catholic Church and the Missouri Synod Lutheran Church joined forces to promote a state constitutional amendment that would allow taxpayer funding of religious schools. Americans United formed a coalition with the Farm Bureau Federation and several churches to oppose the measure, which voters rejected by 57 to 43 percent.

Maryland, 1972: Residents were asked to decide the fate of a proposal to grant $12 million to religious schools through vouchers. They voted it down, 55 to 45 percent. Americans United worked with Protestant, Jewish and other groups through a coalition called the Maryland Committee for Public Education and Religious Liberty to defeat the measure.

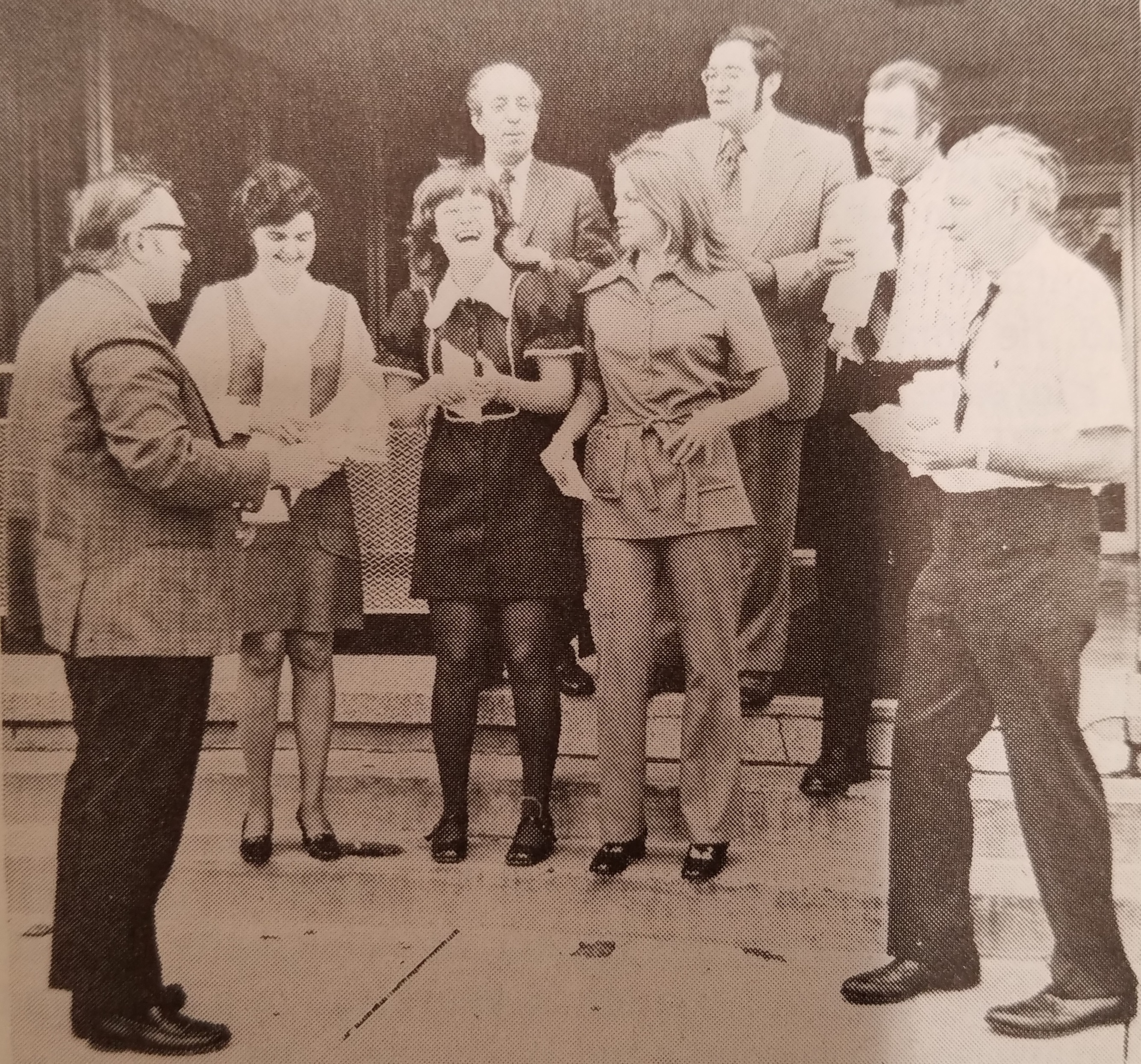

(PHOTO: Americans United staffers head to the polls to stop vouchers in Maryland in 1972.)

Oregon, 1972: Voucher boosters put a measure on the ballot that would have weakened the state constitution’s ban on tax aid to religious schools. Voters rejected it, 69 to 31 percent.

Idaho, 1972: A proposal to change the state constitution to allow limited forms of aid to religious schools, including bus transportation, appeared on the ballot. Voters said no by a margin of 53-47 percent.

Maryland, 1974: Undaunted by their loss in 1972, Maryland lawmakers tried again to funnel tax aid to religious schools, proposing a $10-million package to “loan” books and equipment to private institutions. Americans United reactivated its coalition from two years earlier and led the opposition. Voters rejected the scheme by a higher tally this time, 57 to 43 percent.

Washington, 1975: Pro-voucher religious groups attempted to amend the state constitution to allow unlimited forms of tax aid to religious secondary schools and colleges. John D. Blankinship, a Seattle attorney, worked with Americans United to spearhead the opposition. The amendment, HJR 19, failed, 61 to 39 percent.

Missouri, 1976: Groups that support vouchers won a spot on the ballot for a proposal to remove the Missouri Constitution’s language barring tax aid to sectarian institutions. The vote was held during a primary election in August, which led some to speculate that the measure might pass due to lower turnout. It was handily rejected, 60 to 40 percent. Americans United worked with a group called Missouri Friends of the Public Schools and several other organizations to educate voters about the dangers of the proposal, known as Amendment 7.

Alaska, 1976: Some state officials proposed changing the state constitution to allow tax aid to religious schools. The measure, Proposition 4, was ostensibly pitched as a lifeline to a financially troubled Methodist university in Anchorage, but Americans United pointed out that the language was so broad it would have included religious secondary schools. Voters said no to the measure, 54-46 percent.

Michigan, 1978: A front group calling itself “Citizens for More Sensible Financing of Education,” formed by leaders of the Catholic Church, the Missouri Synod Lutheran Church and the Christian Reformed Church, promoted Proposition H, which would have changed the way education was funded in the state to allow vouchers for private schools. Americans United joined forces with public-education groups, religious organizations, civil-rights groups and others to sound the alarm. Voters crushed the amendment, 74 to 26 percent.

District of Columbia, 1981: A right-wing anti-tax group called the National Taxpayers Union (NTU) won a spot on the ballot for a scheme to establish tuition tax credits, a kind of voucher plan, in the nation’s capital. The group apparently believed that D.C.’s largely African-American population would back the proposal because some of the city’s public schools were troubled. NTU even ran television ads attacking the public schools and portraying them as dangerous. D.C. voters were not swayed, and they trounced the plan, 89 to 11 percent.

California, 1982: Catholic groups in the state pulled together to promote Proposition 9, which would have amended the state constitution to allow millions in tax dollars to be spent on books and other materials for private (mostly religious) schools. Voters said no, by a 69-31 percent margin.

Massachusetts, 1982: Voters were asked to decide the fate of Question 1, which would have allowed taxpayer funds to subsidize “aid, materials or services” to private schools. The voters rejected it, 62 percent against to 38 percent for.

Massachusetts, 1986: Apparently unfazed by their 1982 defeat, pro-voucher groups pushed an even more ambitious scheme called Question 2. Heavily backed by the Archdiocese of Boston, the plan would have weakened the ban on tax aid to religious institutions contained in the Massachusetts Constitution. The Sunday before the election, Catholic churches in Boston were ordered to play a recording by Boston Cardinal Bernard Law instructing congregants to vote for Question 2. The ploy backfired, and voters rejected the scheme 70 to 30 percent.

Utah, 1988: Voucher boosters believed they’d win over voters in this conservative and religious state and put a tuition tax credit referendum known as Initiative C on the ballot. Voters were not impressed and crushed it, 70 to 30 percent.

Oregon, 1990: Libertarian Party activists and others joined forces to put Measure 11, which would have established a sweeping voucher plan in the state, on the ballot. Americans United and other groups worked through a coalition called Oregonians for Public Education and Religious Liberty to defeat the measure. The Oregon fight was notable because big guns from Washington, D.C., weighed in. Vice President Dan Quayle and then-U.S. Rep. Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.) tried to gin up support by holding a $500-a-plate fundraising dinner for the initiative in D.C. in October. On Election Day, the measure fared poorly, losing by a 67-33 percent margin.

Colorado, 1992: Tom Tancredo, an official with the U.S. Department of Education’s regional office in Denver, promoted a voucher initiative known as Amendment 7. The measure received a big push from Lamar Alexander, who was then the country’s secretary of education. Alexander issued an open letter urging Colorado residents to “make Colorado the national leader in a revolution to increase educational opportunities for America’s children.” Americans United worked closely with the No On Vouchers Campaign and sent a fact sheet outlining all of the problems with vouchers to its members in the state. When the results came in, it wasn’t even close: the scheme was defeated by 67 to 33 percent.

California, 1993: Libertarian Party activists linked up with a bevy of Religious Right groups to promote Proposition 174, a sweeping measure that would have repealed the church-state separation provisions of the California Constitution and allocated billions in state funds for a broad voucher scheme. Americans United joined a coalition of educational, religious and civil-liberties organizations opposed to the measure, which failed by a 70-30 percent margin.

Washington, 1996: Deciding to try another tactic, voucher boosters floated Initiative 173, which would have required the state to pay for “scholarships” (in reality vouchers) for students attending private schools. The scheme was bankrolled by Ron Taber, a wealthy retired businessman known for being hostile to public education. Taber poured $1 million into the drive, but voters weren’t fooled by the euphemistic “scholarship” language, and the initiative failed by 65 to 35 percent.

Michigan, 2000: Dick DeVos, president of the Amway Corp. and husband of current U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, bankrolled a scheme to phase in vouchers gradually, starting with pupils attending public schools deemed “failing” in urban districts. The state’s Catholic leaders backed the measure, and U.S. Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) did a TV commercial endorsing the plan. Voters remained unimpressed and rejected the scheme, 69 to 31 percent.

California, 2000: Tim Draper, a Silicon Valley venture capitalist who has called public education “socialistic,” funded a ballot measure that would have essentially privatized education in California. Under Draper’s plan, Proposition 38, every child in the state would have received $4,000 per year to pay for education. Draper poured $26 million into the proposition, at one point boasting that was pocket change to him because it “won’t cut into my lifestyle one bit.” Draper even set up a website offering people prizes if they would endorse the measure. It was all for naught: the plan was easily defeated, 71 to 29 percent.

Utah, 2007: Advocates of public education successfully put a measure on the ballot to roll back a voucher plan that had been passed by the legislature after aggressive lobbying by the American Legislative Exchange Council, a group that promotes far-right bills in the states. Patrick Byrne, the founder of the web retailer Overstock.com, spent at least $3 million to persuade voters to retain the plan. Utahns had other ideas and repealed the scheme, 62 to 38 percent. After the vote, a bitter Byrne lashed out at state residents, asserting that Utah residents “had failed a statewide IQ test. … They don’t care enough about their kids. They care an awful lot about this system, this bureaucracy, but they don’t care enough about their kids to think outside the box.”

Florida, 2012: Americans United and other groups worked hard to educate voters about Amendment 8, a provision that would have removed the church-state separation provisions of the Florida Constitution and paved the way for vouchers. Under Florida law, the measure needed to get 60 percent (three-fifths) approval to pass but fell far short of that, garnering only 45 percent.

Oklahoma, 2016: State legislators proposed stripping language from the Oklahoma Constitution that prohibits public money or property from being used to support religion and religious institutions. The proposal, SQ 790, was pitched as a way to protect display of the Ten Commandments on government property, but voters saw through that and rejected it, 57 percent to 43 percent. (At the same time, voters in Atlantic City, N.J., voted against a non-binding referendum to create a city-wide voucher plan, 54 percent to 46 percent.)

* * *

Ironically, some of the jurisdictions that have so resoundingly rejected private-school subsidy schemes at the ballot box now have voucher plans because legislatures have pushed them through anyway. For example, in Washington, D.C., where voters were adamant about not wanting tuition tax credits in 1981, residents had a voucher plan foisted on them by Congress in 2003. It was described at the time as a five-year “pilot” program but has been reauthorized since then, even though objective studies of the program show that the students attending voucher schools are receiving no academic benefit and some of the schools are of questionable quality.

In Maryland, where voters decisively rejected calls to funnel taxpayer money to private schools on two occasions, legislators in 2016 passed a program that gives vouchers to low-income students. Florida also has a kind of backdoor voucher plan that operates through a complicated scheme of tax credits that are awarded to businesses that donate to entities that grant vouchers.

As the Arizona vote proves, however, legislators who go too far can be reined in. All it takes is enough citizens who care about public education to stand up for our schools.