In 2007, legislators in Texas passed House Bill 1287, which was duly signed into law by then-Gov. Rick Perry. The bill gave public school districts throughout the state the option of offering “elective courses on the Bible’s Hebrew Scriptures and New Testament.”

Texas Freedom Network (TFN), a statewide organization that works to defend separation of church and state, responded by asking Mark Chancey, a professor of religious studies at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, to examine some of the classes that had been created in an attempt to determine what was being taught in Texas classrooms.

One of Chancey’s reports, “Reading, Writing & Religion II: Texas Public School Bible Courses In 2011-12,” looked at Bible classes being offered in 57 school districts and three charter schools. Chancey found a mixed bag. While some school districts were doing a pretty good job of offering objective instruction, others seemed to have veered wildly off course.

In Belton Independent School District, for example, students were being given a pamphlet published by the American Tract Society titled “One Nation Under God.” The pamphlet asserts, “The United States was founded on the principles of liberty in the Holy Bible and the reverence of the Founding Fathers” and adds, “Giving God His rightful place in the national life of this country has provided a rich heritage for all its citizens. Yet, wonderful as the benefits of that heritage may be, a true relationship to God is not a matter of national declaration but rather the personal responsibility of each individual citizen.”

It concluded by asking, “Would you like to place your trust in Jesus Christ and receive Him as your Savior from Sin?”

Belton wasn’t the only the district using problematic materials. Chancey found that some districts were assigning the book Heaven Is For Real, which purports to tell the story of a 3-year-old named Todd Burpo who claims he visited Heaven during a near-death experience. Other districts were screening videos produced by churches or movies made by evangelical Christian firms with clear proselytizing messages.

As Chancey noted, some of this material is “difficult to reconcile with the Supreme Court’s benchmark of an objective approach to the study of the Bible as part of a secular program of education.”

Despite the problems Texas had experienced with Bible classes, such courses are catching on in other states. Several have been introduced in legislatures this year.

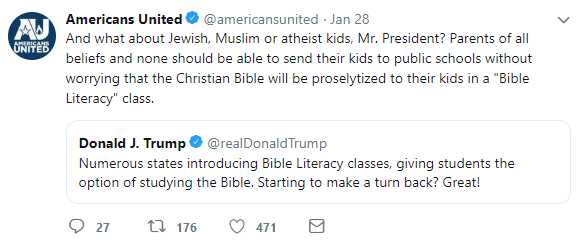

The drive got a boost Jan. 28 when President Donald Trump, apparently motivated to act by a segment on Bible literacy courses aired on Fox News Channel’s “Fox & Friends” program, issued a tweet announcing his support.

“Numerous states introducing Bible Literacy classes, giving students the option of studying the Bible,” wrote Trump. “Starting to make a turn back? Great!”

Trump’s endorsement of the classes caught the media’s attention, and several news outlets ran stories on Bible literacy courses and how they might affect public schools.

Some reporters turned to Americans United for help. In an interview with USA Today, Rachel Laser, AU’s president and CEO, called for caution.

“State legislators should not be fooled that these bills are anything more than part of a scheme to impose Christian beliefs on public schoolchildren,” Laser said.

Laser’s comment captured the concern Americans United and other organizations have over these classes: While they sound acceptable in theory, the implementation often turns out to be highly problematic.

AU says there’s further cause for concern because the current push for Bible literacy courses is being backed by the Religious Right-led Project Blitz. Among the Blitz’s leaders is David Barton, a Texas man who peddles fake “Christian nation” history through books, videos and a website.

Barton and others active in the Religious Right, Americans United maintains, have no interest in seeing truly objective courses about the Bible in America’s public schools. Instead, they hope to use these classes as a vehicle to spread fundamentalist versions of Christianity and inaccurate forms of Christian nationalism.

AU argues that many classes that masquerade as Bible literacy courses are really more like Sunday school classes. Sometimes this is deliberate, and other times it’s simply the product of teachers not being given any training, but the end result is the same: Public school students are exposed to preaching, not teaching.

In theory, there should be no legal bar to teaching about the Bible (or any other religious book) in a public school. In a 1963 Supreme Court ruling that struck down a mandatory, coercive program of prayer and Bible reading in a Pennsylvania public school, the majority made a clear distinction between school-sponsored devotionals and objective instruction about religion.

“[I]t might well be said that one’s education is not complete without a study of comparative religion or the history of religion and its relationship to the advancement of civilization,” observed Justice Tom Clark. “It certainly may be said that the Bible is worthy of study for its literary and historic qualities. Nothing we have said here indicates that such study of the Bible or of religion, when presented objectively as part of a secular program of education, may not be effected consistently with the First Amendment.”

Chancey said he agrees with Clark on the importance of religious literacy, but he has concerns about the approach some legislators have lately embraced.

“I share the view that in our society, biblical literacy is important for a broader cultural literacy,” Chancey told Church & State. “The basic argument that much of Western and world culture and the arts cannot be fully understood without some familiarity with the Bible is irrefutable. I would argue that biblical literacy can also serve an explicitly civic function by helping students understand that ‘sacred texts,’ like all texts, are subject to multiple interpretations, and that even readers and communities that regard them as authoritative disagree on their meaning – an important lesson for a diverse society.

“But it’s essential to emphasize that in a pluralistic society and an age of globalization, biblical literacy is only one component of a much broader religious literacy,” Chancey continued. “That broader religious literacy should prepare students to engage respectfully with fellow citizens of all religious persuasions as well as those with no religious affiliation. Biblical literacy taught for these ends is no stalking horse. That being said, some of the loudest voices calling for using public schools to promote biblical literacy are unhelpfully trying to reduce all religious literacy down to simply biblical literacy. Their goal seems to be to promote their own particular religious views over those of everyone else. That’s a clear case of trying to co-opt public schools into the project of privileging some religions over others and privileging religion in general over non-religion.”

(S)ome of the loudest voices calling for using public schools to promote biblical literacy are unhelpfully trying to reduce all religious literacy down to simply biblical literacy. Their goal seems to be to promote their own particular religious views over those of everyone else. That’s a clear case of trying to co-opt public schools into the project of privileging some religions over others and privileging religion in general over non-religion.

~ Professor Mark Chancey

Indeed, truly objective Bible literacy courses remain elusive. Part of the problem seems to be that some state legislators who sponsor the bills that would create these classes give away the game by outlining goals that are clearly evangelistic in nature.

In Florida, for example, state Rep. Brad Drake gave his reasons for supporting a Bible literacy bill: “A study of a book of creation by its creator is absolutely essential. So why not? It’s the book that prepares us for eternity, and there’s no other book that does that.”

But an objective study about the Bible won’t portray it as a book that prepares people for the afterlife. That’s clearly a devotional approach.

A lack of good teaching materials is another problem. For years, a group in North Carolina called the National Council on Bible Curriculum in Public Schools (NCBCPS) has promoted a curriculum it insists is acceptable for use in public schools.

NCBCPS is, in fact, a Religious Right group with an agenda. It promotes a fundamentalist, literal interpretation of the Bible and incorporates Barton’s “Christian nation” material in its courses.

1994, Elizabeth Ridenour, founder of the group, was asked by the Greensboro News & Record why Bible literacy classes are necessary. She responded with Religious Right boilerplate, remarking, “The reason I feel it is so important is the breakdown of society. We’ve taken the Bible out and put metal detectors in. That speaks for itself.”

The group’s curriculum was being used in a Florida public school in the late 1990s. A group of concerned parents filed a lawsuit, and a federal court ruled that the portion of the curriculum that dealt with the New Testament could not be used. The section involving the Hebrew Bible could be used only if it were substantially revised.

Chancey, who reviewed NCBCPS’s curriculum for the peer-reviewed Journal of the American Academy of Religion, asserted, “The overall level of quality is strikingly low.”

Added Chancey, “The overall impression the various editions convey is of an inability to differentiate between pseudoscience, urban legends, fringe theories, and mainstream scholarship as well as between faith claims and nonsectarian descriptions. … In short, students will leave this course with the understanding of the Bible apparently held by most members of the NCBCPS and with little awareness of views held by other religious groups or within the academic community.”

A group called the Bible Literacy Project (BLP) also produces a curriculum. The colorful, picture-filled tome is titled The Bible And Its Influence. First published in 2006, the book was pulled together by Chuck Stetson, a conservative activist and Republican Party high donor. The group’s advisory board contains several conservative activists, although some moderates have endorsed the book as well. Reviews have been mixed, but most scholars say the tome is much better than what the NCBCPS has on offer.

“Their production values are clearly higher than those of the NCBCPS,” Chancey said. “But in some places, BLP materials lapse into a tone of assumed historicity – that is, the story under discussion is basically an accurate historical account. The overall tone is clearly one of Bible boosterism. The BLP is interested in portraying the Bible solely as a source of positive personal and social transformation.”

It’s unclear how widely used Stetson’s curriculum is. During a recent speech in Australia, Stetson claimed it is used in more than 640 public high schools in 44 states.

A third curriculum was produced by Steve Green, a fundamentalist Christian businessman who founded the Hobby Lobby chain of craft stores. Green’s curriculum has been criticized for its lack of objectivity. One of its chapters is titled “How Do We Know That the Bible’s Historical Narratives are Reliable?” Green himself has admitted that his primary goal is to convey the idea that the Bible’s influence on society has been positive.

In a 2014 column about the Green curriculum, Stephen Prothero, a professor of religion at Boston University, expressed some concerns about it.

Prothero said the curriculum promotes the idea that the Bible’s claims are historically accurate – an assertion many scholars would dispute. The curriculum does this, he said, “through leading questions (‘How do we know that the Bible’s narratives are reliable?’), sometimes through graphics that provide check marks in boxes regarding the text’s ‘reliability’ and ‘historical accuracy,’ and sometimes through maps that, by pinpointing where biblical events occurred, shut down all doubt about their historicity. In one ‘summary’ box, this draft reads: ‘We can conclude that the Bible, especially when viewed alongside other historical information, is a reliable historical source.’”

Concluded Prothero, “I do not doubt that Green’s team sincerely wants to produce a non-sectarian textbook. I am skeptical, however, that the scholars that Green has assembled for this job – a group that tilts like a listing ship toward evangelicals working at evangelical institutions – are capable of producing a textbook beholden to facts rather than faith.”

Green said he hoped to see his curriculum in wide use in public schools, but it doesn’t look like that’s happening. Officials at the Mustang, Okla., public school system had planned to use it, but they dropped the idea late in 2014 after Americans United and the Freedom From Religion Foundation expressed concerns.

Curricula like this underscore one of the most challenging dimensions of the biblical literacy debate: How to teach the text using a “warts and all” approach.

While most mainline Christians don’t assert that the Bible is without error, fundamentalists do – which means they accept its historical claims as well. This is a problem because scholarly research has cast doubt on some of the fundamentalists’ claims. For example, most New Testament scholars now agree that the gospels aren’t contemporary accounts of the life of Jesus, and that they were written decades after his death. But to teach this in a public school in the Bible Belt would be to court controversy.

In Chancey’s view, these are some of the thorniest issues presented by the push for Bible classes, and he points out, “Courts have noted that to teach the Bible as straightforward history is to promote a particular Christian interpretation of the Bible.”

To get around the problem, Chancey told Church & State that he recommends the following approach: “A teacher should acknowledge it upfront and focus on what stories reveal about the ancient authors and communities that created them and how those stories function in contemporary religious communities. For example, a teacher could say, ‘Clearly belief in Jesus’ resurrection is central to understanding the circles of Christianity that produced the gospels, the evolution of Christianity over time, and different circles in Christianity today. Given legal parameters and the diverse sensibilities of our community, our task in a public school setting is not to determine whether the resurrection stories are historically accurate but to explore their significance for understanding the development of Christianity.’”

As this issue of Church & State was going to press, another Bible literacy bill surfaced – this one in Missouri. State Rep. Curtis Trent (R-Springfield), told the Springfield News-Leader, “[S]tudents should know how Christianity has played a role in our history. It gives you a fuller understanding of why historic actors did what they did and how history has evolved.”

Americans United will monitor this bill, along with similar measures in other states.